Vladimir Rodzianko - The Real Ghost of Rasputin |

|||||

Author Lionel Rolfe recalls time spent in Chiswick with the Russian composer

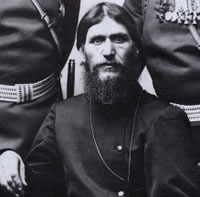

I first met Vladimir Rodzianko nearly 40 years ago. He lived in a house in Chiswick outside of London, where his father also lived, one of the most famous of Russian Orthodox priests. Father and son had the same name, writes Lionel Rolfe. The elder Rodzianko had been born Vladimir Rodzianko in the Ukraine in 1915 and he had an amazing study where he did his work, so beloved by many in the Orthodox community. It was a small cubbyhole under the stairs and it was filled from floor to ceiling with icons. Rodzianko, who later went to San Francisco where he became His Grace the Right Reverend Bishop Basil Rodzianko in the Orthodox Church in America, at that time, was the most prominent Russian Orthodox leader in England. This was in part because he broadcast religious commentary to his home country during the Cold War on the BBC, and it was probably no coincidence that the junior Vladimir became the Russian voice of the BBC in addition to being a composer of some notoriety. Poor Vladimir was saddled with me by my mother, the pianist Yaltah Menuhin, who felt that because she had performed his avant garde aleotoric music, had the right to ask him to give me a place to live while I worked on a biography of my family. My mom was not a fan of most avant garde music, regarding it as pretentious and puerile. She spoke with mild disdain about Rodzianko’s far-out music, which consisted of musical motifs drawn on mobiles which turned in the wind generated through the open windows at the top of the studio. She then was supposed to improvise on each theme, which she did. Rodzianko the younger felt obligated to my mom because she had played well, and no doubt this feeling of gratitude included not just the quality of her work but the fact that a Menuhin had performed his music. For her part, my mom found Rodzianko amusing, and described him as writing quite pleasant and competent ballet music at the Royal Ballet School where he was employed. This, of course, was a mild put down, but still affectionate. ......... I arrived on the doorsteps in Chiswick, baggage in hand, and was greeted at the door by Rodzianko the junior who was a tall dark man with a big black beard worthy of Rasputin - whom he definitely looked like. And the looks were not untruthful - he was a kind of Rasputin in more ways than just looks. Rodzianko was proud of his background. His grandfather was Mikhail Rodzianko, the last President of the Duma just before the Bolsheviks took over. Rodzianko was of a landowning family, a major ally of the Czars, which had put him on Lenin’s hit list. During the time I lived at Chiswick, Vladimir was constantly getting phone calls. All the papers wanted to interview him after the critics from the biggest London newspapers had given him rave reviews for the music he had written for the Robert Cohan choreographed “Mass,” which was sung by the dancers themselves with multitudinous moans and screams. The work was described as “a general requiem for the victims of man.” ......... The other thing about this great Rasputin-like character, he had a certain sadness about him. For 17 months or so, he had been world famous. The Soviet Union’s most famous ballerina, Natalia Makarova, defected from the Kirov Ballet while in London. At first, the newspaper headlines had her defecting because of Rodzianko. Later she said no, she defected because she wanted to perform newer and more contemporary works than she was allowed to do in the Soviet Union. Her arrival in the West was not entirely auspicious. She lost the chance to perform before Queen Elizabeth when she tore a muscle in her thigh. She also left behind a mother, a stepfather, two husbands as well as devoted colleagues to come live with Rodzianko, who had helped her defect. She was in his arms for nearly two years before she broke off her engagement with Rodzianko, who had become her manager and closest confidant as well as lover. She began missing her family and friends in the Soviet Union. She went to Paris to once again partner with Rudolf Nureyev in Swan Lake. They had danced together for many years at the Kirov in Leningrad until he had defected to the west a decade or so before she did. But the two great Russian dancers had a falling out. “I don’t want to talk about it. . . . I had an unfortunate experience with him,” she said. Then she married a multimillionaire husband and moved to San Francisco, leaving behind a broken hearted Vladimir. The last time I saw Rodzianko, he was still lamenting the loss of the great love of his life. I never regained contact with him, and I’ve noticed that he seems to have disappeared into the woof and warp of London cultural history. He no longer is the toast of the town, or living amidst the headlines. Still, to me, he will always remain the real Rasputin. The full article by Lionel Rolfe can be read here. Rolfe is the author of several books, including Literary L.A., about which a documentary is being made. His other books include Fat Man on the Left, The Uncommon Friendship of Yaltah Menuhin and Willa Cather, The Menuhins: A Family Odyssey, among others. January 18, 2011 |